America and Its Great White Hopes

South Carolina's Black women, Caitlin Clark, and America's great white hopes.

As I watched the WNBA Draft last night, my thoughts continuously returned to the closing moments of the 2024 Women's NCAA Tournament Championship.

The air was thick with the frenetic energy of triumph and despair. A team composed predominantly of young Black women, led by a Black woman coach, from a school in a 40% Black Southern city was celebrating. While tears of defeat were flowing from a team of predominantly young white women, led by a white woman coach, from a school in a 76% white Midwestern city. An inherently racial dichotomy captured and broadcast to millions.

South Carolina's victory should have been a jubilant affirmation of coach Dawn Staley and her team, a celebration of the magic and prowess of Black women and girls. These athletes, through sweat and strategy, had earned not just a title but a moment of unreserved acclaim. Yet, the narrative that unfolded in the wake of their win seemed as though much of the nation was intent on doing anything but celebrating them.

While South Carolina had won, the cameras, those unblinking eyes that feed the nation’s insatiable appetite for narrative and affirmation, lingered only briefly on the victors. Instead, they found Caitlin Clark and her teary-eyed teammates around her, a narrative pivot away from the celebration to the figures of defeat walking off the court. The same happened on social media, where many outlets chose to center Caitlin Clark and Iowa rather than the actual champions. The winners were relegated to the periphery of their own triumph.

In fact, popular sports outlet, Barstool, didn’t even bother to post a single time about South Carolina’s win. Though they posted about the UConn men’s team winning their national championship a day later, and about Caitlin Clark multiple times over the past week.

It is here, in this redirection and erasure, that one finds a picture not merely of a game concluded, but of a larger, more insidious story being told.

Indeed, Clark is a phenomenal athlete, easily the finest in college basketball this season, transcending the boundaries of the women’s league to stand taller than even the men’s league. She will also be a phenomenal pro in the WNBA. Caitlin Clark’s impact stretches beyond the parquet floors where college basketball unfolds, into the realms where cultural icons are forged and admired. Her ascent in women’s basketball is a testimony not only to her undeniable skill, as she masterfully commands the game, akin to orchestrating a complex symphony, but also to how she is perceived and celebrated in the wider context of America's racial and cultural landscape.

Many amplify her image and flock to witness her play not solely for the grace of her three-pointers or the strategic sharpness of her game management but because she embodies something deeply embedded in the American psyche—the desire for a “Great White Hope.” This term, heavy with historical weight, encapsulates the longing for a white savior in realms dominated, historically and presently, by Black and brown people. In sports, this narrative is both subtle and overt; it whispers in the undertones of media praise and shouts in the allocation of endorsements and attention.

This reality created by America’s desire for Great White Hopes has been spoken to by both Hailey Van Lith and Paige Bueckers, white standouts on predominantly Black women’s basketball teams—LSU and UConn. They have lent their voices to the conversation, articulating a consciousness of how the spotlight shines more favorably on them. Their commentary unveils a landscape where the optics of race craft both privilege and narrative.

Van Lith, herself preparing to leave LSU, a stage where her presence among Black excellence has been both highlighted and hyper-analyzed, has spoken to the disproportionate lens through which she is viewed. The adoration she receives, she has noted, is tinged with an undertone that elevates her competitive spirit into something almost saintly, contrasting starkly with the tougher, often less forgiving narratives penned about her Black teammates.

In response to an LA Times article, Van Lith said:

“Some of the words in that article were very sad and upsetting... calling us basically the 'dirty debutantes' that has nothing to do with sports… A lot of the people that are making those comments are being racist towards my teammates, and I’m in a unique situation where I see it myself. I’ll talk trash, and I’ll get a different reaction than if Angel (Reese) talks trash. So, it’s really up to me to, it’s not up to me, but I have a duty to my teammates to have their back.”

Paige Bueckers mirrors this sentiment. So much so, that she dedicated her 2021 ESPYs speech to Black women:

“With the light that I have now as a White woman who leads a Black-led sport and celebrated here, I want to shed a light on Black women,” said Bueckers, the reigning national player of the year. “They don’t get the media coverage that they deserve. They’ve given so much to the sport, the community and society as a whole and their value is undeniable.”

What Hailey and Paige highlighted is the reason why Caitlin Clark can yell at a referee, trash talk another player, take shots that would widely be seen as poor decisions, and generally show competitive fire while remaining an American darling. All while Black players such as LSU’s Angel Reese were looked down upon for the same fire, and USC’s Juju Watkins was blasted in the media for those same shots. It is why after Iowa lost the National Championship to LSU in 2023, First Lady Jill Biden floated the idea of still inviting Caitlin Clark and her teammates to the White House. An unprecedented invitation for a losing team.

In fact, when after LSU defeated Iowa in the National Championship and Angel Reese dared to engage in the same kind of trash talk that Caitlin Clark, her white counterpart, has often deployed without repercussion, the response she received was both alarming and revealing. Reese, a talented Black athlete, found herself not just criticized for her boldness on the court but also targeted with death threats. This severe reaction exposes the deep-seated racial biases that persist in how Black athletes are perceived and treated compared to their white counterparts.

The same biases rooted in why the media did not focus on South Carolina’s team beginning the season unranked, or them going 38-0 despite having the toughest schedule in college basketball, nor the fact that coach Dawn Staley now has the most championships for a Black coach in D1 basketball history, or the many other storylines about this wonderful Black team. Instead the media focused on the tears of Iowa’s young white women. Which makes sense, as white women’s tears have always been a catalyst for white sympathies and rage.

And in the few instances when Dawn Staley and her team were the focus, it was largely centered around Dawn’s praise of Caitlin Clark, or an attempted “gotcha” moment, when a conservative “journalist” tried to back Dawn into a corner by asking her perspective on trans women playing women’s basketball. Which didn’t work, as she beautifully defended trans people. In other words, America has focused overwhelmingly on everything but South Carolina’s wonderful season.

Yet, none of this is inherently Caitlin Clark’s fault. It is, rather, a mantle placed upon her by the historical currents of white America—a country still running on its treadmill of sins, each of which plays a pivotal role in shaping perception and valuation of public figures and athletes. Clark’s basketball greatness, while remarkable, cannot be disentangled from her whiteness. Because it is that whiteness that not only helps elevate her visibility and marketability—but also allows white people to praise her, while demonizing and diluting the excellence of the Black young women in her sport.

The focus on her in the immediate aftermath of the championship loss is emblematic of a cultural reflex that reaches beyond the hardwood.

In the long sweep of America's battle with its conscience, sports have often served as both mirror and battleground. The notion of the Great White Hope arises not merely from a societal desire but from a historical urgency to reaffirm certain myths of racial superiority that feel threatened in times of change. This narrative has been recycled and repackaged with each generation.

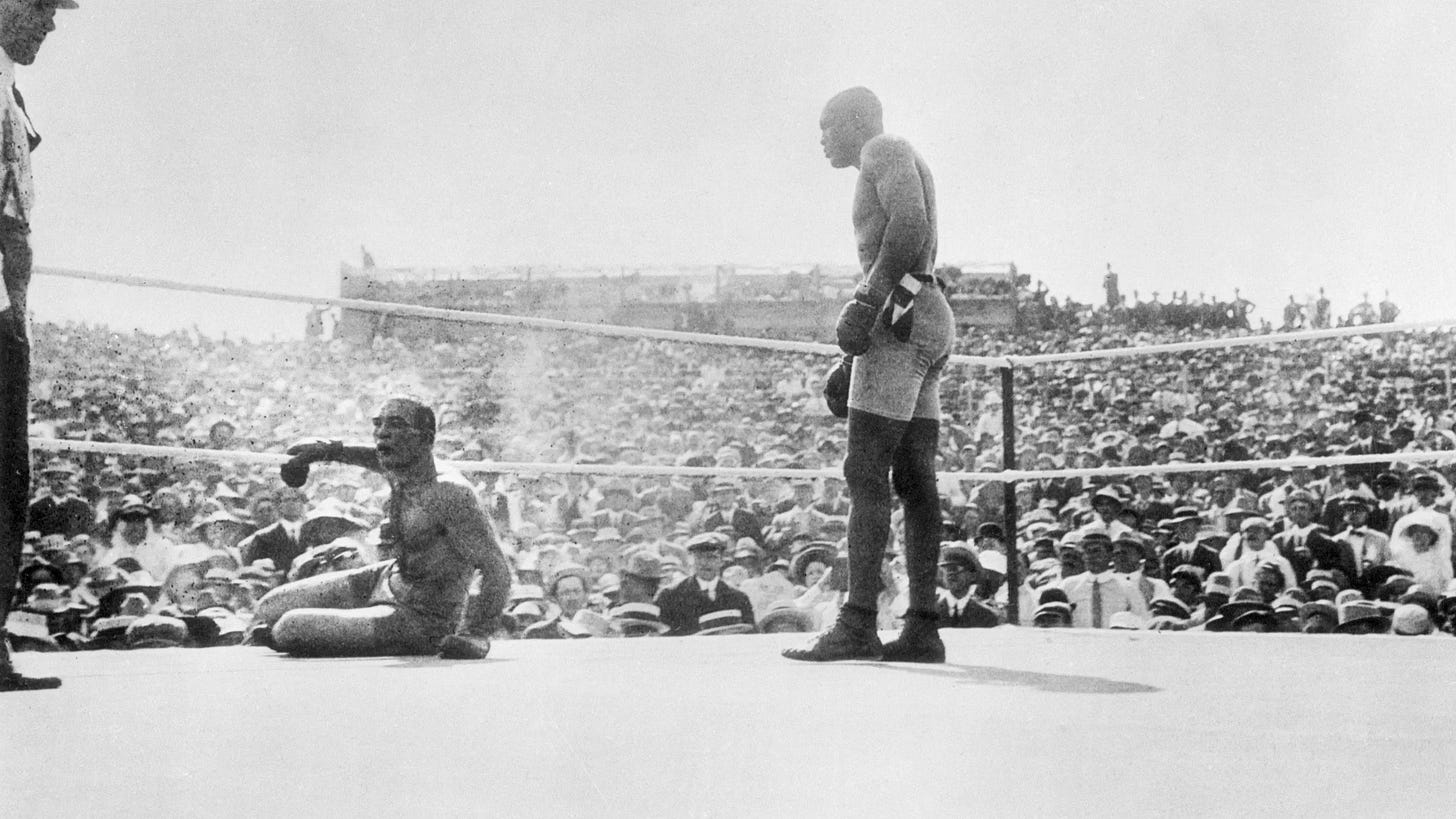

Jack Johnson, who became the first African American world heavyweight boxing champion in 1908, ignited a national and racial panic that underscored the American story at its most honest and ugly. His dominance in the ring, his defiance outside of it, and his unapologetic breach of racial boundaries through marriages to white women, summoned the collective fears of a white society grappling with the specter of Black superiority. In response, a frenzied search began for a Great White Hope to topple Johnson, to restore the racial order that his victories had dared to disrupt. The term itself became synonymous with a desperate yearning to reclaim an imagined past of uncontested white dominance.

The story echoes into the era of Larry Bird in the 1980s, at a time when the NBA was perceived to be dominated by Black athletes. Bird entered the league not merely as a prodigious talent, but as a symbol through which white America could engage with a sport that was increasingly being defined by Blackness. His rivalry with Magic Johnson—framed often as the hardworking, lunch-pail hero from Indiana against the flashy showmanship of the urban, Black star—was not just a sports narrative but a cultural dialogue, filled with racial undertones. Bird's excellence was undeniable, his competitive fire unquenchable, yet the lens through which he was viewed often magnified these qualities to mythic proportions, positioning him as the embodiment of white hopes and a counterbalance to the prevailing Black dominance in the NBA and beyond.

These instances are more than mere footnotes in sports history; they are chapters in the larger American narrative of race. They reflect a pattern of elevating white athletes as symbols of moral and physical excellence when Black athletes dominate the field. This pattern reveals less about the actual abilities of the athletes than it does about the anxieties of a white public, and the narratives the media constructs and perpetuates to appease these anxieties.

Thus, when the spotlight lingers on Caitlin Clark even in defeat, or when it fixates on the tears of Iowa's young white women rather than celebrating the triumphs of South Carolina’s Black athletes, we are witnessing not an isolated incident but a recurring theme. It is a theme as old as the championship itself, one that reaches back to Jack Johnson, passes through Larry Bird, and lands in our present moment, reshaping how heroes are chosen and how stories are told. In this way, the Great White Hope continues to serve as a way to sooth a collective anxiety while subtly challenging the strides toward equality and recognition made by Black athletes.

Yes, Caitlin Clark is great—maybe the greatest of the era so far, a beacon for many in white America, a shimmering example of what they have yearned to see. Her skills on the basketball court are undeniable, her presence magnetic. But she lost. And in that loss, there is an unyielding fact that demands recognition: the Black women who stood against her, who played with the weight of history pressing down upon their shoulders, were better. Not necessarily in individual skill, but as a team in the moment that mattered.

To say they were better is not to engage in a racial victory lap; it is merely to state a fact as clear as the scoreboard at game’s end. But America, with its complex ledger of racial debts and credits, often finds such simple truths too simplistic for Black people. It is not enough for Black women to win; they must win in a manner that comforts, that reassures, that does not challenge the established narratives too deeply — or their white heroes. South Carolina’s victory should be celebrated not because they are Black and Caitlin Clark is white, but because on that day, under those bright lights, they were the superior players. It’s as simple as that.

Yet, as is so often the case, “better” does not hold the same weight when the victors are Black and the vanquished is white. For much of America, the narrative is uncomfortably inverted when Black excellence asserts itself over white hope. This is the irony laid bare for those who claim that Black people are the ones who always make everything about race. It is not those who are oppressed that weave race into every narrative; it is those who stand to lose from racial equality, who fear the world in which their assumed superiority is nullified by the simple, profound truth of a game well played.

The reluctance to celebrate Black women, the hesitance to allow their triumph to be the story, is a mirror reflecting the greater American dilemma. For how can a nation so steeped in the mythos of meritocracy, so proud of its supposed embrace of rugged individualism, reconcile itself with a preference for narratives that elevate the white underdog in defeat over the Black champion in victory? This contradiction does not merely play out on basketball courts or in sports arenas; it seeps into the fabric of daily life, coloring the interactions between the governed and the governors, the justice seekers and the law keepers.

In the refusal to fully acknowledge the victory of South Carolina, what we see is more than bias—it is the throbbing heartbeat of America’s unresolved racial saga. It pulses through the country’s veins. Each refusal to celebrate these athletes properly is not just a missed opportunity for praise; it is an active reinforcement of the old guard, a nod to the ghosts of a segregated past that whisper, “This is not how it should be.”

In recognizing the triumph of South Carolina’s team, America is tasked with confronting its biases, with questioning the foundations upon which we build our heroes and our myths.

April is National Poetry Month, and as such I’d like to share a poem from my forthcoming poetry collection, “We Alive, Beloved.” Which is available for preorder everywhere by click thing this link. Remember preorders are deeply important for marginalized authors. Preorder numbers tell booksellers and the media that a book has the potential of being successful and should be invested in.

This is exactly why we have to 1. Know who we are. 2. Understand our value. 3. Affirm ourselves and each other. 4. Be able to know when to tell people to Fu.. Off.

Thank you. You've explained the dissonance I have been feeling throughout women's basketball the past couple of years. I need to chew on this a while. Again, thank you. I appreciate your thoughtfulness.